High Tibial Osteotomy — A Joint-Preserving Option for Active Patients

Introduction

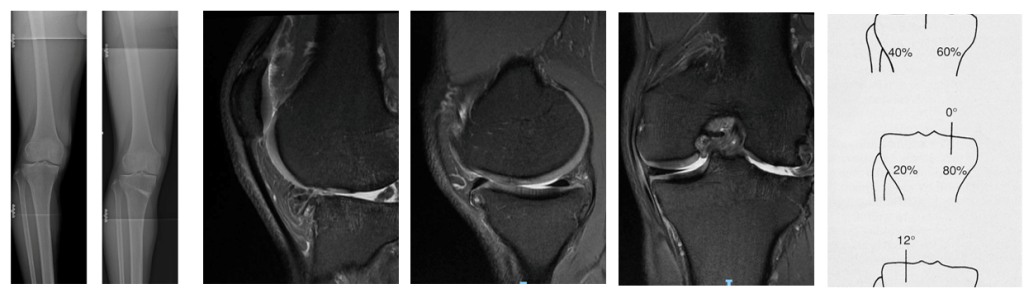

High Tibial Osteotomy (HTO) is a surgical procedure used to correct varus deformity of the knee or to manage recurrent instability after failed anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction (ACLR). In particularly in cases with a steep posterior tibial slope (>12°) (Winkler et al., 2022).

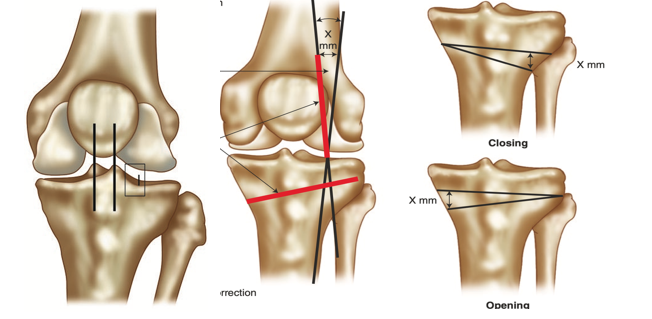

By realigning the mechanical axis of the lower limb, HTO unloads the damaged medial compartment and can restore more physiological joint mechanics (Murray, Winkler, Shaikh, & Musahl, 2021). The procedure is most commonly performed as a medial opening-wedge osteotomy, where a controlled cut is made in the upper tibia and opened to the desired correction angle.

In select cases, particularly after multiple ACL failures, an HTO can reduce the posterior tibial slope to limit anterior tibial translation and graft stress (Winkler et al., 2022). For active individuals with unicompartmental degeneration or instability, HTO serves as a joint-preserving alternative to total knee arthroplasty (Parvizi et al., 2013).

The International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery, and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine has formulated guidelines for indications and contraindications to high tibial osteotomy (HTO).

“Indications for considering HTO in the elite athlete include malalignment with associated joint pathology, after all other possible treatments have been explored.

Osteotomy may improve symptoms, relieve pain, and allow a return to a “normal” lifestyle—that is, one not specifically on competition, although that may be a consideration, Warme, 2021, Sports Health”

HTO rehabilitation

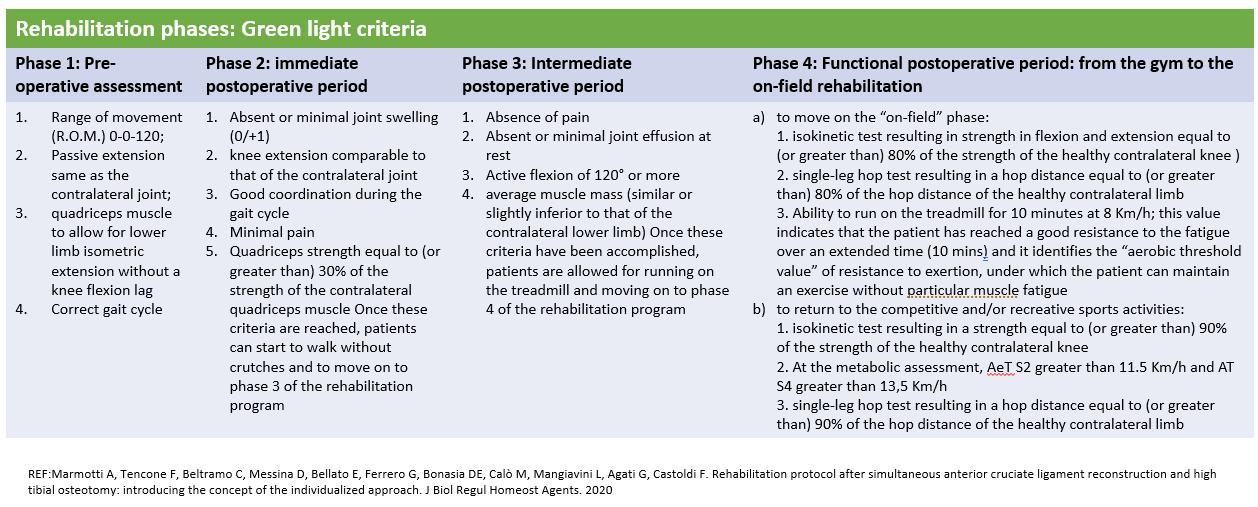

Rehabilitation after HTO follows a criteria-based progression rather than fixed timelines. The goal is to protect the osteotomy site while gradually restoring motion, strength, and limb control (Kumagai & Otoshi, 2021).

Early phase (0–6 weeks):

-

Protected or partial weight-bearing for 1–2 weeks, depending on fixation stability.

-

Early range-of-motion and quadriceps activation exercises begin on day 1.

-

Avoid excessive loading, twisting, or impact; cycling and squats are typically deferred until bone union is confirmed radiographically.

Intermediate phase (6–12 weeks):

-

Gradual return to full weight-bearing.

-

Emphasis on gait retraining, single-leg stability, and progressive quadriceps strengthening.

-

Begin low-impact cardiovascular activity (bike, elliptical).

Advanced phase (3–6 months):

-

Strength ≥ 80 % of the uninvolved limb.

-

Hop and balance progression once pain-free and radiographic union is confirmed.

-

Running or agility work usually delayed until ≥ 6 months.

Return-to-sport criteria (6–12 months):

-

Symmetrical strength and hop performance (≥ 85–90 %).

-

No effusion or tenderness.

-

Patient confidence restored for sport-specific movement.

Return to Sport Rates

Return-to-sport (RTS) rates after HTO are encouraging across multiple populations.

-

In younger adults, 80–90 % return to some level of sport within 6–12 months (Nicolini et al., 2021; Hoorntje et al., 2017).

-

However, only 40–60 % regain their preinjury performance level (Maeda et al., 2021; Katagiri et al., 2022).

-

Among patients over 70 years, 91 % returned to sport—mostly low-impact activities such as golf or walking (Otoshi et al., 2021).

-

When combined with osteochondral allograft transplantation, 79 % returned to sport, though fewer than half achieved their previous intensity (Liu et al., 2020).

These results show that HTO allows meaningful sport participation—even at elite or recreational levels—when realistic timelines and structured rehab are followed.

Patient Expectations

Setting expectations is critical. HTO is not designed to guarantee elite-level return, but rather to relieve pain, restore function, and prolong joint life.

Patients should expect:

-

Gradual improvement over 6–12 months.

-

Residual stiffness or mild discomfort may persist initially.

-

Activity modification toward low- or moderate-impact sports may be required (Warme, Aalderink, & Amendola, 2011).

In contrast to total knee replacement—where only two-thirds of young patients report “normal feeling” knees—HTO patients generally maintain a more natural joint sensation and functional stability (Parvizi et al., 2013).

Outcome Measures

The success of your outcome depends on a structured, progressive rehabilitation plan tailored to your goals, sport, and strength profile.

Choose a physiotherapist who has a plan with you. Someone who tests you regularly and adjusts your program accordingly. Choose someone with a handhold dynometer and a force plate.

References

-

Hoorntje, A., Witjes, S., Kuijer, P. P. F. M., Koenraadt, K. L. M., van Geenen, R. C. I., Daams, J. G., Getgood, A., & Kerkhoffs, G. M. M. J. (2017). High rates of return to sports activities and work after osteotomies around the knee: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(11), 2219–2244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0721-0

-

Katagiri, H., Shioda, M., Nakagawa, Y., Ohara, T., Ozeki, N., Nakamura, T., Sekiya, I., & Koga, H. (2022). Risk factors affecting return to sports and patient-reported outcomes after opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy in active patients. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 10(9), 23259671221118836. https://doi.org/10.1177/23259671221118836

-

Liu, J. N., Agarwalla, A., Christian, D. R., Garcia, G. H., Redondo, M. L., Yanke, A. B., & Cole, B. J. (2020). Return to sport after high tibial osteotomy with concomitant osteochondral allograft transplantation. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(9), 2266–2274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546520920626

-

Maeda, S., Chiba, D., Sasaki, E., Oyama, T., Sasaki, T., Otsuka, H., & Ishibashi, Y. (2021). The difficulty of continuing sports activities after open-wedge high tibial osteotomy in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis: A 2-year-minimum follow-up. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics, 8(68). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-021-00385-4

-

Murray, R., Winkler, P. W., Shaikh, H. S., & Musahl, V. (2021). High tibial osteotomy for varus deformity of the knee. JAAOS Global Research & Reviews, 5(7), e21. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00141

-

Nicolini, A. P., Christiano, E. S., Abdalla, R. J., Cohen, M., & Carvalho, R. T. (2021). Return to sports after high tibial osteotomy using the opening-wedge technique. Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia, 56(3), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1715514

-

Otoshi, A., Kumagai, K., Yamada, S., Nejima, S., Fujisawa, T., Miyatake, K., & Inaba, Y. (2021). Return to sports activity after opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy in patients aged 70 years and older. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 16(576). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02718-6

-

Parvizi, J., Nunley, R. M., Berend, K. R., Lombardi, A. V., Ruh, E. L., Clohisy, J. C., & Barrack, R. L. (2013). High level of residual symptoms in young patients after total knee arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 472, 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3229-7

-

Warme, B. A., Aalderink, K., & Amendola, A. (2011). Is there a role for high tibial osteotomies in the athlete? Sports Health, 3(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738109358380

-

Winkler, P. W., Murray, R., Shaikh, H. S., & Musahl, V. (2022). A high tibial slope, allograft use, and poor patient-reported outcome scores are associated with multiple ACL graft failures. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 30(8), 2845–2854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06676-8