Safety concern when using blood flow restriction (BFR)

Introduction

The objective of the blogpost is to assess the safety and potential side effects of Blood flow restriction (BFR) training clinical application to patients with early post operative conditions.

Blood flow restriction (BFR) training involves the use of cuffs placed proximally around a limb, with the aim of maintaining arterial inflow while occluding venous return during exercise (Scott et al. 2015). When combined with low-intensity resistance exercise, BFR has been reported to promote similar hypertrophy and strength gains as moderate to heavy load and lower joint forces/stress in a manner comparable with that of high-intensity resistance exercise in healthy adults.

At rest, cuff pressure is slowly increased until the flow of blood is no longer detected, a term frequently referred to as total limb occlusion pressure (LOP) or arterial occlusion pressure (AOP). A submaximal percentage (eg, 40%-80%) of that pressure is prescribed for the exercise session as this method allows for appropriate progression of the pressure, similar to the way progressive loading resistance training (Bond, 2018).

Since the first publication in 1987 on the effect of BFR training (Eiken, 1987) many studies have highlighted the important role BFR training may play in rehabilitation settings to optimize recovery after surgery (Rolnick, 2021). The physiological mechanisms behind these muscle adaptations include acute muscle cell swelling, increased anabolic hormone production, altered muscle fiber-type recruitment associated with hypoxia and fatigue, decreased myostatin, decreased atrogenes, and satellite cell proliferation, increased cell signaling for pathways related to muscle protein synthesis and decreased cell signaling for pathways resulting in muscle protein breakdown (Minniti, 2019; Bond, 2018, Nascimento et al 2022).

However, there has been a concern on how safe BFR training are when introduced early after post op procedure as most studies have stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria, leaving limited data on individuals with comorbidities frequently seen in rehabilitation clinics (Nascimento et al 2022).

To address this the clinician can ask (Nascimento et al 2022).:

- Is my patient like the participants in the studies with BFRT?

- Does BFRT have a clinically relevant benefit (e.g., improved function or hypertrophy) that outweighs the potential risks of application?

- Is another treatment or method available that could provide similar results with less risk than BFRT?

From a national survey on the safety of KAATSU training the occurrence ratio of side effects was as follows: subcutaneous hemorrhage (13.1%), numbness (1.297%), cerebral anemia (0.277%), cold feeling (0.127%), venous thrombus (0.055%), pulmonary embolism (0.008%), rhabdomyolysis (0.008%), deterioration of ischemic heart disease (0.016%) (Fig. 9 and table 1). In addition, fainting has occurred in rare cases, and hypoglycemia has been reported (Nakajima, 2006). Numbness is likely due to inappropriately high tourniquet pressures, thus resulting in peripheral nerve compression. Therefore, appropriate selection and application of the cuff (i.e., size, site, pressure) is essential for preventing peripheral nerve irritation (Vanwye et al. 2017). The most frequently used cuff width is 10 to 12 cm, although cuffs greater than 15 cm may be more desirable (Bond, 2019). Furthermore, low load BFR training with healthy individuals and older adults with heart disease found no change in blood markers for thrombin generation or intravascular clot formation (Vanwye et al. 2017).

In a recent review (Minniti, 2019) on the safety and potential adverse events related to the use of BFR in patients with musculoskeletal disorders. A large number of studies did not even address safety and therefore could not be included in this review. The majority of the RCTs that were included were conducted in patients with knee-related musculoskeletal conditions. Of the 152 patients who received BFR as an intervention, no one experienced a rare adverse event, and only 4 experienced common adverse events. These events are comparable with the adverse events seen in patients who receive traditional resistance training interventions (Minniti, 2019).

Safety concerns

It is strongly recommended to review of the patient’s medical history, the signs, and symptoms indicative of underlying disease be used to avoid undesirable. Pre-screening questions or questionnaires that are included in the documentation for a new client’s or patient’s initial evaluation might help to make some clinical decisions, while others depend on an individual and physical examination.

Three primary areas of concern relating to BFR training identified in the literature are venous thromboembolism (VTE), potentially excessive hemodynamic/cardiovascular responses and muscle damage. Understanding what the available literature has demonstrated regarding these concerns is paramount to use of BFR safely and will assist practitioners in the manipulation of variables such as load, pressure, effort, and volume to further the safety profile (Rolnick, 2021).

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE): The concern regarding the potential for BFR to increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which may present as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), remains for some clinicians, especially for their postsurgical patients (Bond, 2018)

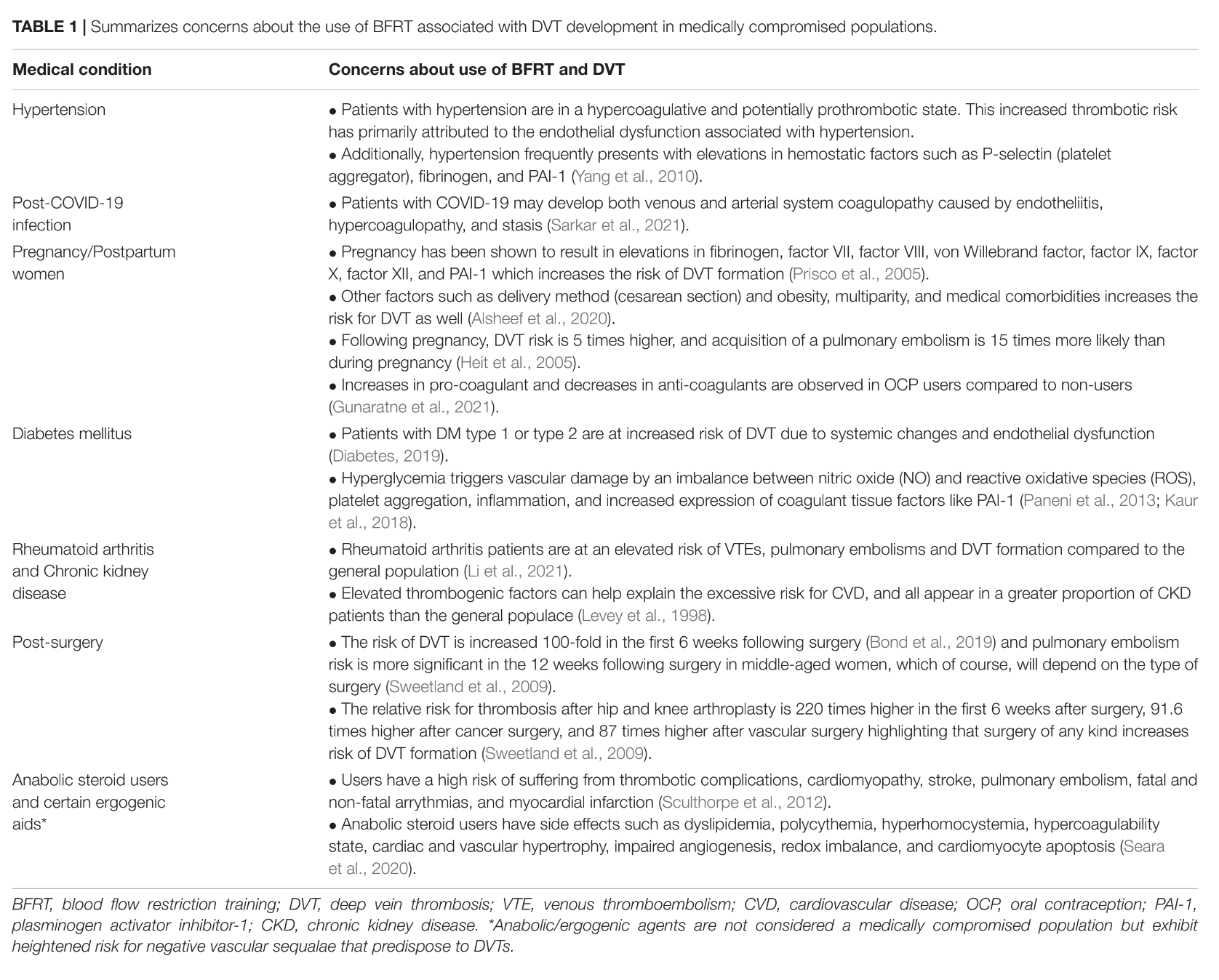

Nascimento et al 2022 have summarizes the concerns about the use of BFRT associated with DVT development in medically compromised populations in table 1.

- And further risk factor assessment of thrombosis in table 2

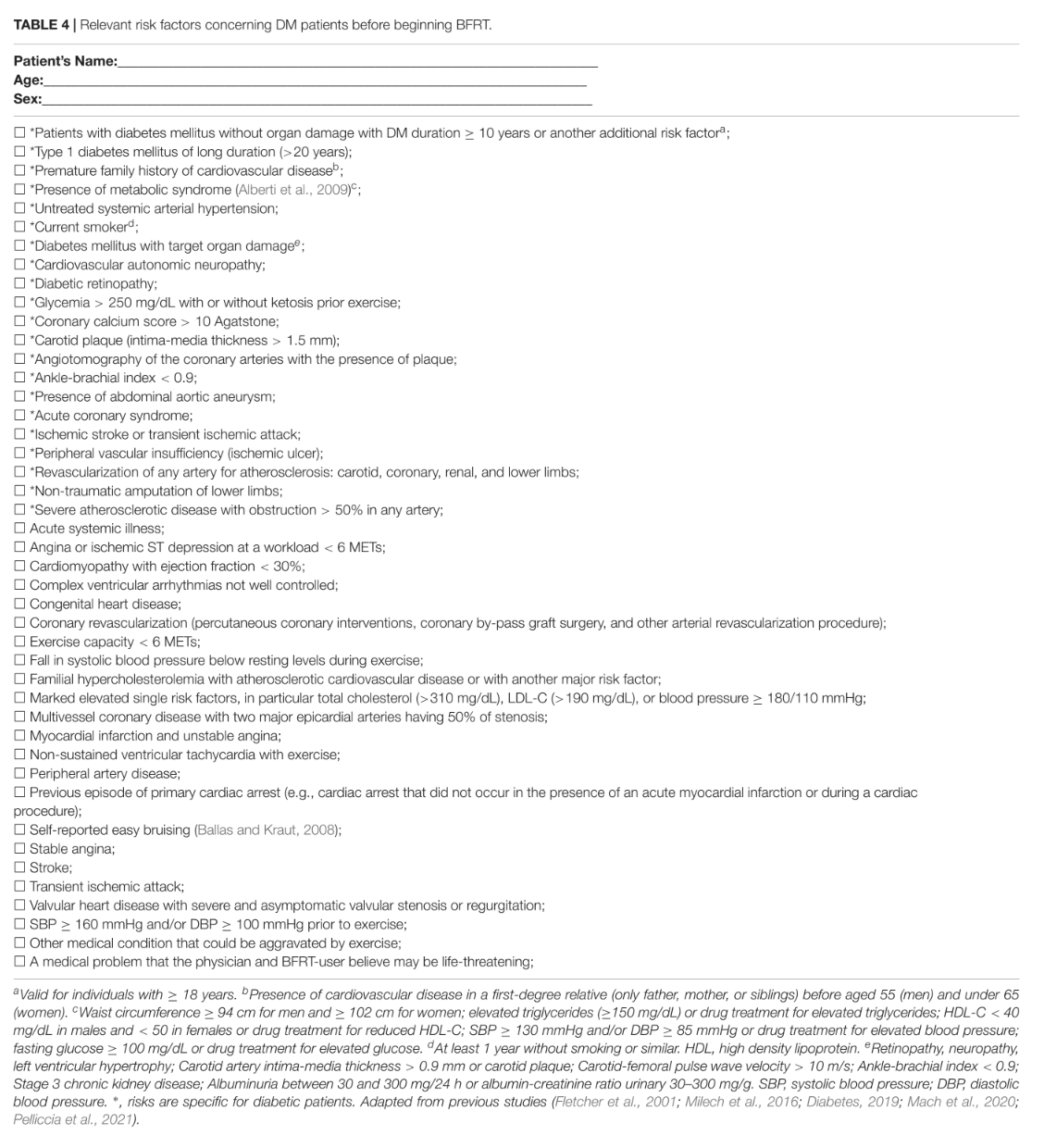

- Relevant risk factors concerning Diabetes patients before beginning BFRT in table 4.

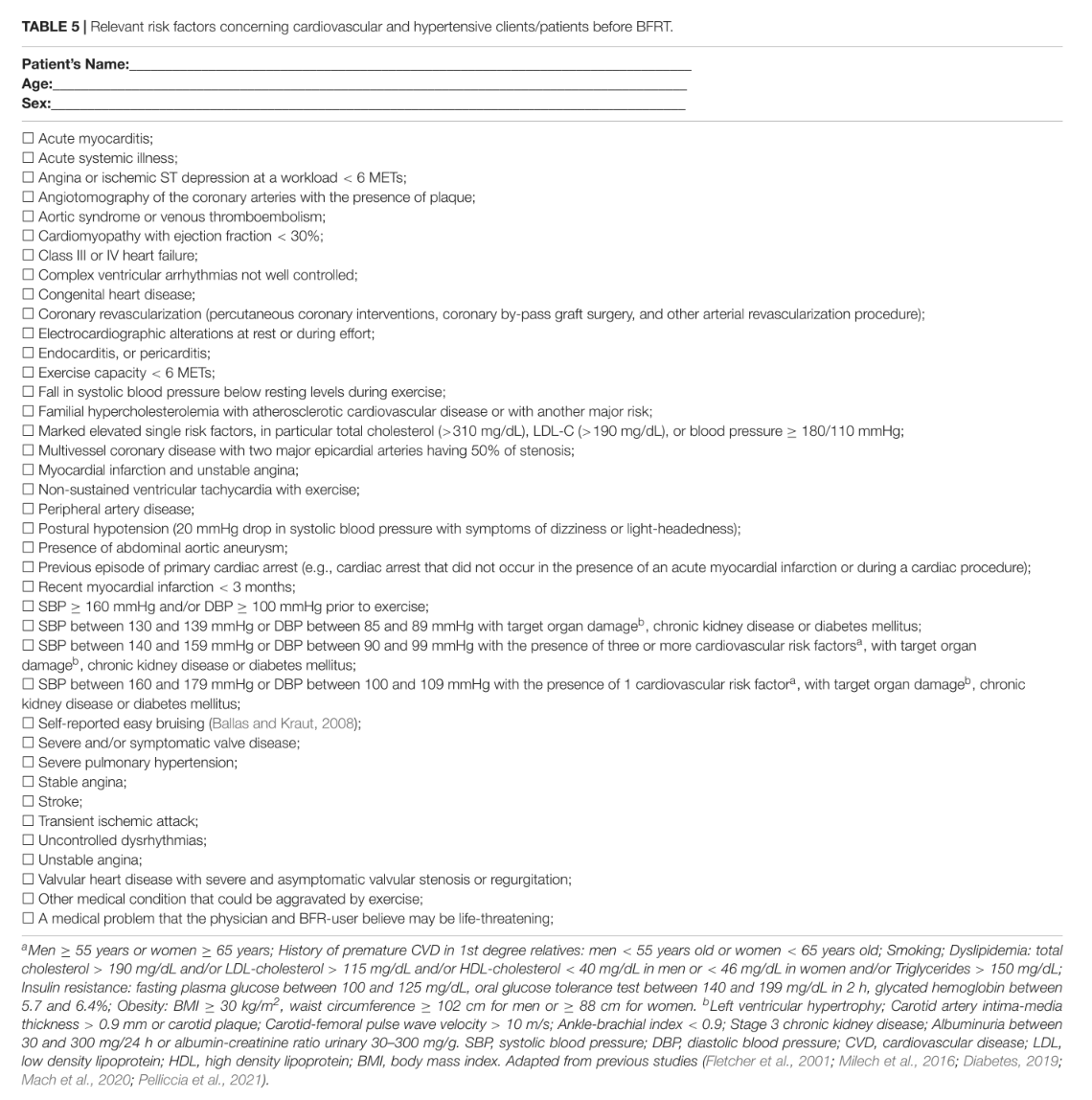

- Relevant risk factors concerning cardiovascular and hypertensive clients/patients before BFRT in table 5.

- Risk factors concerning rheumatoid arthritis patients before BFRT in table 6.

- Risk factors concerning apparently healthy individuals before BFRT in table 7.

Barriers for Blood Flow Restriction Pressure

There are many different ways BFR can be used which can lead to lack of understanding of safety concern (Rolnick, 2021).

Rolnick, 2021, have developed a clinical decision funnel for the inclusion or exclusion of use of BFR as a musculoskeletal rehabilitation framework that allows a reasoned evidence-based decision. In this funnel the physician needs to reasoning if the use of BFR is related to a loading problem or pain problem.

There next the physician should consider clotting considerations. One way of screening for possible contraindications related to VTE risk for patients following surgery is mentioned above. Another used flow chart for clotting consideration is demonstrated here (Rolnick, 2021).

Take home points

Is it safe to use BFR early after surgery? Yes, however, ask yourself the three leading questions.

- Is my patient like the participants in the studies with BFRT?

- Does BFRT have a clinically relevant benefit (e.g., improved function or hypertrophy) that outweighs the potential risks of application?

- Is another treatment or method available that could provide similar results with less risk than BFRT?

Do the patient have a specific condition then use some of the above mentioned questions or flow charts.

Here are four classic examples of early BFR after surgery. Practical implementation for BFR on post op ACLR or early weight bearing restrictions after cartilage or meniscus repair in the knee joint.

Reference:

- Eiken O, Bjurstedt H. Dynamic exercise in man as influenced by experimental restriction of blood flow in the working muscles. Acta Physiol Scand. 1987;131(3):339-345.

- Scott BR, Loenneke JP, Slattery KM, Dascombe BJ. Blood flow restricted exercise for athletes: a review of available evidence. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(5):360-367.

- Bond CW, Hackney KJ, Brown SL, Noonan BC. Blood Flow Restriction Resistance Exercise as a Rehabilitation Modality Following Orthopaedic Surgery: A Review of Venous Thromboembolism Risk. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019

- Rolnick N, Kimbrell K, Cerqueira MS, Weatherford B, Brandner C. Perceived Barriers to Blood Flow Restriction Training. Front Rehabil Sci. 2021 Jul 8;2:697082. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2021.697082. PMID: 36188864; PMCID: PMC9397924

- Vanwye WR, Weatherholt AM, Mikesky AE. Blood Flow Restriction Training: Implementation into Clinical Practice. Int J Exerc Sci. 2017 Sep 1;10(5):649-654. PMID: 28966705; PMCID: PMC5609669.

- Nascimento DDC, Rolnick N, Neto IVS, Severin R, Beal FLR. A Useful Blood Flow Restriction Training Risk Stratification for Exercise and Rehabilitation. Front Physiol. 2022 Mar 11;13:808622. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.808622. PMID: 35360229; PMCID: PMC8963452.

- Minniti MC, Statkevich AP, Kelly RL, Rigsby VP, Exline MM, Rhon DI, Clewley D. The Safety of Blood Flow Restriction Training as a Therapeutic Intervention for Patients With Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review. Am J Sports Med. 2020 Jun;48(7):1773-1785. doi: 10.1177/0363546519882652. Epub 2019 Nov 11. PMID: 31710505.

- Nakajima, T., Kurano, M., Iida, H., Takano, H., Oonuma, H., Morita, T., Meguro, K., Sato, Y., & Nagata, T. (2006). Use and safety of KAATSU training:Results of a national survey. International Journal of Kaatsu Training Research, 2, 5-13.

[…] BFR and safety. See here Safety concern when using blood flow restriction (BFR) […]