Blood flow restriction after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

Abbreviations

- BFR = Blood flow restriction

- BFRT = Blood flow restriction training

- LOP = Limb occlusion pressure

- AOP = Arterial occlusion pressure

- NMES = Neuromuscular electrical stimulations

- ACL = Anterior Cruciate Ligament

- ACLR = Anterior Cruciate Ligament reconstruction

- MVC = Maximal voluntary contraction

- RPE = Rate of perceived exertion

- DOMS = Delayed onset muscle soreness

Table of Contents

- Preamble

- The classic guidelines

- Determined total limb occlusion pressure (LOP) or arterial occlusion pressure (AOP)

- Low or high occlusion pressure and 15-20% or 30% of 1RM

- Weekly frequency

- BFR and RPE / discomfort.

- Cuff size and straight or contour cuff

- BFR and Safety

- BFR and in the initial phase of ACLR

- Scenario 1)

- Scenario 2)

- Scenario 3)

- Scenario 4)

- Scenario 5)

- BFR and NMES

- BFR and aerobic activities

- BFR for pain

- BFR and preoperative rehabilitation

- BFR and tendons

- Aspetar BFR guideline

- References

Preamble

Blood flow restriction training (BFRT) can best be understood as a physiological shortcut to achieve muscle growth (hypertrophy), strength gains and improved functional level, with minimal strain on tendons but still enough to allow increased cross-sectional of the tendon (Centner et al., 2023). Therefore, BFRT has been commonly used for physiotherapist and strengthening and conditioning coaches for rehabilitation or used an option for athletes to maximize muscle hypertrophy gains (Nicholas Rolnick & Schoenfeld, 2020; Scott, Loenneke, Slattery, & Dascombe, 2016)

During BFRT, a cuff is applied proximally to the leg on the affected side. The cuff is inflated to a set pressure, and the pressure in the cuff will restrict the arterial inflow (the oxygenated blood flowing out to the muscle) and minimize the venous return (the deoxygenated blood flowing away from the muscle) (Patterson et al., 2019)

Loss of muscle mass (muscle atrophy), muscle strength, and level of function is common in people who have undergone surgery for ACLR. Specific, patients with an ACL tear can lose between 20% and 33% in m. quadriceps muscle volume from the time of injury until 3 weeks after their ACLR (Wengle et al., 2022). Rehabilitation may be initiated early to limit loss of muscle mass, knee flexor and knee extensor strength, and to maximize long-term knee stability and function of the knee joint (Spada, Paul, & Tucker, 2022).

In the initial early phase after ACLR, where the patient can be load-compromised by having restrictions with range of motion or weight bearing, experience swelling or pain, traditional heavy strength training is not feasible. BFRT can offer an effective alternative solution to achieve some of the same responses as heavier progressive strength training while minizine the mechanical load of the knee joint (Hughes, Paton, Rosenblatt, Gissane, & Patterson, 2017).

In the literature, a distinction is often made between muscle atrophy because of inactivity/immobilization (disuse muscle atrophy), and loss of muscle mass as a consequence of acute trauma to joints and/or muscles after an injury or surgery such as ACLR.

In disuse muscle atrophy, the loss of muscle mass is explained by the fact that the ratio between muscle protein synthesis (anabolic signaling) and muscle protein breakdown (catabolic signaling) shifts towards a net greater breakdown, primarily explained by a reduction in muscle protein synthesis (Lepley, Davi, Burland, & Lepley, 2020). Patients with load restrictions, such as requires immobilization, will experience disuse muscle atrophy. Often, load restrictions for one joint will affect the load possibilities for an entire extremity, which is why a loss of muscle mass is observed in the entire extremity, especially the weight-bearing muscles. BFRT can probably reduce disuse muscle atrophy thereby making it easier for the patient to protect against disuse muscle atrophy by accelerates muscular exhaustion with either using time or number of repetitions to failure (Farup et al., 2015; Kubota, Sakuraba, Sawaki, Sumide, & Tamura, 2008; Takarada, Takazawa, & Ishii, 2000).

Muscle atrophy as a result of ACL injury is more complex and is due to multifactorial conditions in the affected leg. Especially, when extensive neural inhibition can occur. Acute changes in the nervous system because of an ACL injury or ACLR can decouple nerves from muscle tissue (denervation), reducing the ability for muscle contraction and making it difficult to activate the muscle during exercise (Lepley et al., 2020).

According to Aspetar’s’ ACL guidelines five studies have evaluated the effect of additional low load BFRT after surgery compared with usual rehabilitation. From these studies it seems Low load BFRT might improve quadriceps and HS strength and prevent disuse atrophy at the early phase and there was a large effect on swelling and subjective pain reduction during training (Kotsifaki et al., 2023).

The classic guidelines

An often-recommended guidelines for BFRT was described by (Patterson et al., 2019) as illustrated below. However, you need to question yourself. What do you want to achieve with BFRT. BFRT is a method to facilitate getting into fatigue. We will in the followed discussed some of the point that can be relevant for your patient.

| Frequency | 2–3 times a week (>3 weeks) or 1–2 times per day (1–3 weeks) |

| Load | 20–40% 1RM |

| Restriction time | 5–10 min per exercise (reperfusion between exercises) |

| Type | Small and large muscle groups (arms and legs/uni or bilateral) |

| Sets | 2-4 |

| Cuff | 5 (small), 10 or 12 (medium), 17 or 18 cm (large) |

| Repetitions Pressure | (75 reps) – 30 × 15 × 15 × 15, or sets to failure 40–80% AOP |

| Rest between sets | 30–60 s |

| Restriction form | Continuous or intermittent |

| Execution speed | 1–2 s (concentric and eccentric) |

| Execution | Until concentric failure or when planned rep scheme is completed |

| Based on (Patterson et al., 2019) | |

Determined total limb occlusion pressure (LOP) or arterial occlusion pressure (AOP)

When applying BFRT we use a submaximal percentage (eg, 40%-80%) of total limb occlusion pressure (LOP) or arterial occlusion pressure (AOP). This method allows for appropriate progression of the pressure, similar to the way progressive loading resistance training (Bond, Hackney, Brown, & Noonan, 2019). There is a common belief that BFRT is more effective when the cuff pressure is individually adjusted to LOP/AOP. There are several ways to determined LOP/AOP. Many devices offer automatically calibration to determine the desired LOP/AOP. However, the barrier to these devices are they are often more costly and sometimes practical issues can occur. Also, you need to be aware of the AOP ability to identify AOP. A recent study (Keller, Faude, Gollhofer, & Centner, 2023) showed that automatic low-cost device reached its maximum pressure capacity in 70% in the legs, making the results on the legs unreliable and was not recommended for use at the legs because of its limited pressure capacity (Keller et al., 2023).

In this case manual pump can be used to inflate the cuff to the desired level. To determined total LOP/AOP you will place the cuff as proximal as possible on an extremity. Then you place the patient in a supine position with 0° knee extension. With our Doppler device you are locating the arterial blood flow on either the dorsalis pedis artery or the posterior tibial artery on the foot to monitor arterial flow distal. Next, you slowly increased the cuff until the flow of blood is no longer detected. This is normally above 200mmhg. From this point you then lower the pressure to your determined 40-80%. However, BFRT is a method to facilitate getting into fatigue. Getting into the fatigue “chasing the pump” can properly be achieved in several percentage of AOP. This is giving the patient some time to adapt to BFRT by slowly increasing the %-LOP/AOP before 80% is reach.

Auto-regulation in blood flow restriction strength training: more than just a fancy phrase

Low or high occlusion pressure and 15-20% or 30% of 1RM

Increased metabolic stress has been postulated as a potential mechanism of hypertrophy after BFRT. In systematic review (de Queiros, de França, et al., 2021) there were a trend when comparing 40-50% vs 80-90% of AOP/LOP indicated that higher pressure induces more fatigue (MVC torque decline) when using 15-20% of 1RM, but not in 30% of 1RM. In addition, both exercises at 40-50% vs 80-90% showed to induce more fatigue compared to low-load exercises without BFR. Therefore, even percentage of AOP with moderate values (40-50%) may be sufficient to induce an adequate stimulus in addition to higher levels that might cause discomfort as long the exercises is performed with loads between 30-40% of 1RM.

Weekly frequency

BFRT is recommended to be performed 2-3 times per week (low frequency) when interventions last longer than three weeks. For shorter intervention, less than 3 weeks the recommendation can increased to 1-2 times per day (high frequency) (de Queiros, Rolnick, de Alcântara Varela, Cabral, & Silva Dantas, 2022). In ACLR most intervention is high frequency with blocks of eight to 14 weeks (Hughes et al., 2019; Jack et al., 2022; Ohta et al., 2003; Prue et al., 2022). Furthermore, a high frequent dose, five times per week appears to maximize hypertrophic adaptations in well trained powerlifters (Bjørnsen et al., 2019), therefore short periods of high frequency BFRT may be a strategy for maximizing hypertrophy. The most practical way would be to followed previously used frequencies in ACLR is to add 1–2 exercises for target muscle group at the end of a heavy-load training session, as a finisher, to preferentially stress muscle fibers that may not be sufficiently stressed with the goal to improving muscle strength and muscle mass. The combination of heavy load and low-load BFR in a single training session have been hypothesized to positively contribute to maximal increases in hypertrophy (de Queiros, Rolnick, de Alcântara Varela, et al., 2022; Nicholas Rolnick & Schoenfeld, 2020). To begin an intervention with BFRT depends of your clinical case, but we don’t have research for more than four months, so it would be recommended to stop or pause BFRT after 3-4 months or earlier if the athlete can tolerate to go into heavier strength training or get fatigue with heavier strength load, then BFR can be stop or paused.

BFR and RPE / discomfort

Rate of perceived exertion (RPE) has been defined in the literature as “the conscious sensation of how hard, heavy, and strenuous a physical task is. Whereas exertion encompasses how strenuous a task is, discomfort is related to the perception of physiological and unpleasant sensations associated with exercise that may include pain. It is speculated that this increase in RPE is mediated by greater accumulation of fatigue during BFR exercise. Thus, monitoring RPE, a systematic review and meta-analysis (de Queiros, Rolnick, Dos Santos Í, et al., 2022) on BFR and RPE shown no differences in RPE or discomfort between low load with BFR versus non-BFR high load. However, as BFR can generates exercise-induced discomfort/pain, patient education may be an important component of long-term compliance. Based of the experience from the Aspetar ACL Group the load can be increased if the patient report less than RPE 6.

Cuff size and straight or contour cuff

Cuff shape and size shown to impact the amount applied pressure and comfort. The most frequently used cuff width is 10 to 12 cm, although cuffs greater than 15 cm may be more desirable (Bond, 2019). Contour cuff shapes are longer at the top and shorter at the bottom, creating a closer fit on the limb due to differences in diameter. However, the difference in proximal to distal diameter of a contoured cuff reduces AOP slightly (~5.9 mm Hg) compared to a straight cuff (Nicholas Rolnick, Kimbrell, & Queiros, 2022)

BFR and Safety

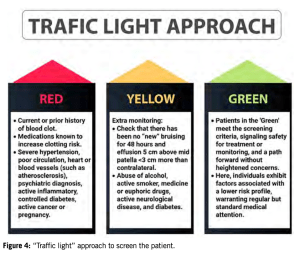

When applying BFRT safely we need to have some precautions as most studies have stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria, leaving limited data on individuals with comorbidities frequently seen in rehabilitation clinics (Nascimento, Rolnick, Neto, Severin, & Beal, 2022). To address these precautions the clinician can ask if BFRT have a clinically relevant benefit (e.g., improved function or hypertrophy) that outweighs the potential risks of application? Is another treatment or method available that could provide similar results with less risk than BFRT? (Nascimento et al., 2022).

DOMS is one of the most reported symptoms after BFRT. However, even though DOMS was higher reported in some studies, there were no difference between edema and DOMS (de Queiros, Dos Santos Í, et al., 2021). From a national survey on the safety of KAATSU training the occurrence ratio of side effects was as follows: subcutaneous hemorrhage (13.1%), numbness (1.297%), cerebral anemia (0.277%), cold feeling (0.127%), venous thrombus (0.055%), pulmonary embolism (0.008%), rhabdomyolysis (0.008%), deterioration of ischemic heart disease (0.016%). In addition, fainting and hypoglycemia has only occurred in rare cases (Nakajima, 2006). Numbness is likely due to inappropriately high tourniquet pressures, thus resulting in peripheral nerve compression. Therefore, appropriate selection and application of the cuff (i.e., size, site, pressure) is essential for preventing peripheral nerve irritation (Vanwye, Weatherholt, & Mikesky, 2017). In a recent review (Minniti et al., 2020) on the safety and potential adverse events related to the use of BFRT in patients with musculoskeletal disorders. Many studies did not address safety and therefore could therefore not be included in this review. Of the 152 patients who received BFRT no rare adverse event was found, and only four experienced common adverse events. These events are comparable with the adverse events seen in patients who receive traditional resistance training interventions (Minniti et al., 2020). In addition no change in blood markers for thrombin generation or intravascular clot formation for healthy individuals and older adults with heart disease found (Vanwye et al., 2017)

Three primary areas of concern relating to BFR training identified in the literature are venous thromboembolism (VTE), excessive hemodynamic/cardiovascular responses and muscle damage. Understanding what the available literature has demonstrated regarding these concerns is paramount to use of BFR safely and will assist practitioners in the manipulation of variables such as load, pressure, effort, and volume to further the safety profile (N. Rolnick, Kimbrell, Cerqueira, Weatherford, & Brandner, 2021).

One way of screening for possible contraindications related to VTE risk for patients following a surgery (N. Rolnick et al., 2021). It is our recommendation that standardized BFRT is safe. However, as we are limit the blood flow to the leg, we do need to have precaution if you

- Have high blood pressure (hypertension), diabetes, and/or get bruising easily.

- Have problems with your heart or blood vessels (such as atherosclerosis).

- Have a neurological disease.

- Have a psychiatric diagnosis that prevents you from exercising regularly.

- Have an abuse of alcohol, medicine or euphoric drugs.

- Have cancer.

- Have an active inflammatory state in the body (septic active infection).

- Are pregnant.

BFR and in the initial phase of ACLR

- Scenario 1)

Jack, 2022, (Jack et al., 2022), published their proposal on how occlusion training can be integrated into an existing 12-week rehabilitation plan for 32 patients undergoing ACLR with BTB graft starting from week 2 post op. The patients were divided into two groups for 1) traditional rehabilitation (CONTROL, n=15) and 2) rehabilitation in combination with occlusion (BFR, n=17).

The difference between the two interventions was that the BFR group had to complete 8 selected rehabilitation exercises from the traditional rehabilitation protocol, under partial suppression of blood flow, at 80% (AOP). The 8 exercises each consisted of four sets divided into 30-15-15-15 repetitions at 20% of 1RM with a 30-second rest between each set. The rehabilitation plan was initiated from week two after surgery. The most important findings were that the bone mass was significantly better preserved in the BFR group compared to the control group (Measured by DXA scanning).

| Post Op week | Exercise | Set, reps, time | Session per week | Load | Tempo |

| 2 | Quadriceps contractions | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 3 | Quadriceps contractions or standing terminal knee extension | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 4 | terminal knee extension or bilateral leg press | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 5 | Terminal knee extension, bilateral leg press or Seated Hamstring Curl | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 6 | Single Leg Press or Seated Hamstring Curl | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 7 | Single Leg Press, Seated Hamstring Curl or Squat | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 8 | Single Leg Press, Seated Hamstring Curl or Squat | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 9 | Single Leg Press, Seated Hamstring Curl or Split Lunges | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 10 | Single Leg Press, Seated Hamstring Curl or Split Lunges | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 11 | Single Leg Press, Seated Hamstring Curl or Box Step ups | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 12 | Single Leg Press, Seated Hamstring Curl or Box Step ups | 30/15/15/15 reps | No info | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| Based on (Jack et al., 2022) | |||||

- Scenario 2)

Prue and colleagues (Prue et al., 2022) demonstrated that even BFRT used around one week post op on adolescents (15y, with the youngest 12y) showed minor side effects such as itchiness. Although this study had a relatively high dropout rate, this could have been due to 80% LOP being used from the beginning. A gradual increase in LOP can be recommended in the first sessions in especially adolescents.

| Post Op week | Exercise | Set, reps, time | Session per week | Load | Tempo |

| 1-2 | 1) Quadriceps contractions

2) Side Lying Hip Abduction 3) Prone hip extension |

1) 10 seconds on, 10 second rest

2) 30/15/15/15 reps 3) 30/15/15/15 reps |

Two session per week | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 3-4 | 1) Long Arc Quad (90-30deg)

2) Side Lying Hip Abduction 3) Leg press shuttle (Total gym) |

1) 30/15/15/15 reps

2) 30/15/15/15 reps 3) 30/15/15/15 reps |

Two session per week | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 5-6 | 1) Long Arc Quad (90-30deg)

2) Bilateral Hip Bridge 3) Leg press shuttle (Total gym) |

1) 30/15/15/15 reps

2) 30/15/15/15 reps 3) 30/15/15/15 reps |

Two session per week | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 7-8 | 1) Step Up

2) Bilateral Hip Bridge 3) Leg press shuttle (Total gym) |

1) 30/15/15/15 reps

2) 30/15/15/15 reps 3) 30/15/15/15 reps |

Two session per week | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| 9-12 | 1) Split Squat

2) Medial step down 3) Leg press shuttle (Total gym) |

1) 30/15/15/15 reps

2) 30/15/15/15 reps 3) 30/15/15/15 reps |

Two session per week | 80% of LOP | Slowly 1–2 seconds |

| Based on (Prue et al., 2022) | |||||

- Scenario 3)

Hughes (Hughes et al., 2019) used BFRT eight weeks (total 16 sessions) compared to heavy strength training. Patients were allowed to begin when they met criteria for leg press which included the ability to 1) unilaterally weight bear without pain for≥5 s without support, 2) demonstrate a knee ROM of 0–90°, 3) perform repeated straight leg raises without knee extension lag, 4) demonstrate gluteal and knee muscle activation, and 5) minimal effusion change with activity. Here the BFRT and heavy strength training induced comparable gains in muscle hypertrophy and muscle strength (10RM and isokinetic strength). The BFRT led to greater improvement in physical function level and knee ROM compared to heavy strength training. The BFRT group also led to greater reductions in knee pain (KOOS) and knee swelling compared to heavy strength training. There were no serious side effects associated with the two exercise interventions. No changes in knee laxity were recorded. On the basis of the results, the authors conclude that BFRT are advantageous in the early progressive loading phase after ACLR, especially for patients with knee pain and who experience swelling of the knee during activity.

| Post Op week | Exercise | Set, reps, time | Session per week | Load | Tempo |

| 4-12 | 1) Unilateral leg press | 1) 30/15/15/15 reps | Up to five time per week | 80% of LOP | Slowly |

| Based on (Hughes et al., 2019) | |||||

- Scenario 4)

Ohta et al (Ohta et al., 2003) used home-based BFRT from week two, 6x per week for a total of 16 weeks in addition to standard training. In practice, the training was performed almost without any problems for the first 10 minutes after BFR was started, but some patients felt discomfort or a dull pain in the lower limb during BFR after about 12 minutes, although there were individual differences. Patients were instructed to relieve the BFR after a maximum of 15 minutes, stop for 15–20 minutes and then resume the training. In this study, 24 patients were initially enrolled, but two patients dropped out because of discomfort or a dull pain in the lower limb. However, no other complications were reported.

| Post Op week | Exercise | Set, reps, time | Session per week | Load |

| 2-4 | 1) SLR

2) Sidelying hip abduction 1-kg weight was attached to the foot joint |

1) 5 sec and repeated 20 times x 2 set

2) 5 sec and repeated 20 times x 2 set |

6x times per week | Around 180mmhg |

| 5-8 | 1) SLR with

2) Sidelying hip abduction 2-kg weight was attached to the foot joint |

1) 5 sec and repeated 20 times x 2 set

2) 5 sec and repeated 20 times x 2 set |

6x times per week | Around 180mmhg |

| 2-12 | Hip joint adduction exercise by holding a ball between both knees | were maintained for 5 sec at maximum effort, repeated 20 times | 6x times per week | Around 180mmhg |

| 5-16 | Half-squat exercise | maintaining half-squatting position for 6 sec, repeated 20 times x 2 times daily | 6x times per week | Around 180mmhg |

| 5-16 | Step-up exercise (25 cm in height) | repeated 20 times x 3 times daily. Week 7–8, a 4- to 6-kg load was held with both hands; weeks 9–12, an 8- to 10-kg load; weeks 13–16, a 12- to 14-kg load). |

6x times per week | Around 180mmhg |

| 9-16 | Elastic tube exercise bending the knee from 45 to 100 degrees, | 1x 20 reps daily in week 9-12

2x 20 reps daily in week 13-16 |

6x times per week | Around 180mmhg |

| 13-16 | Knee-bending walking | 3 set of 60 steps | 6x times per week | Around 180mmhg |

| Based on (Ohta et al., 2003) | ||||

- Scenario 5)

Jakobsen, T. L, 2022 (Jakobsen, Thorborg, Fisker, Kallemose, & Bandholm, 2022) used BFRT from week 4 when early weight bearing restrictions after cartilage or meniscus repair were contraindicated. Here the patients were using BFRT 5x per week for a total of 9 weeks in addition to training. No adverse effect was recorded, and it seems that the group that applied may prevent disuse thigh muscle atrophy during a period of weight bearing restrictions.

| Post Op week | Exercise | Set, reps, time | Session per week | Load | Tempo |

| 4-13 | 1) Seated Knee Extension

2) Prone Hamstring Curl |

1) 30/15/15/15 reps

2) 30/15/15/15 reps |

Up to five time per week | 80% of LOP | 2 seconds to extend the leg to a horizontal position, 1 second to hold the position, 2 seconds to lower the leg again and 1 second to relax. |

| Based on (Jakobsen et al., 2022) | |||||

BFR and NMES

Another popular modality to avoid muscle disuse atrophy is the use of Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES). A few studies have combined BFRT and NMES on thigh muscle with good effect. Slysz (Slysz et al., 2021) investigate the effects of repeated application of BFR+NMES on healthy individual for preserving skeletal muscle mass and strength during a period of limb disuse. It was hypothesized that repeated BFR+EMS treatment would be more effective than repeated BFR treatment without NMES for attenuating the loss of quadriceps mass and knee-extension strength during a 14-day leg unloading period. They concluded, the combined treatment of BFR+NMES preserves muscle mass during a period of limb disuse, while BFR treatment without EMS did not protect against this expected disuse atrophy. Similar conclusion had Natsume, (Natsume, Ozaki, Saito, Abe, & Naito, 2015) with eight untrained young male participants showing that low-intensity NMES training, when combined with BFR, induces muscular hypertrophy and concomitant increases in isometric and isokinetic strengths in stimulated muscles.

| Week | Exercise | Set, reps, time | Session per week | Load | Tempo |

| 2 weeks intervention | Passive | Circulatory occlusion lasted 5 min and was performed three times, each separated by 5 min of reperfusion | Five times per week, two times daily for 14 days. | Tourniquet pressure ranged from 180 to 290 mm Hg across participants | The EMS protocol consisted of a duty cycle of 6 seconds on (stimulation) and 15 seconds off (no stimulation) with the pulse width set at 200 μs and the stimulation frequency set at 60 Hz. |

| Based on (Slysz et al., 2021) | |||||

| 2 weeks intervention | Passive | Four sets of BFR (each of 5 min) with 1-min rest intervals between sessions. Cuff air pressure was released immediately upon completion of each session | The target pressure for each subject was calculated based on midthigh circumference (50 cm, 140 mmHg. 50– 55 cm, 160 mmHg. 60 cm, 200 mmHg | The stimulation frequency and duty cycle were approximately 30 Hz and 8 seconds of stimulation followed by a 3 seconds pause. The intensity of electrical flow was selected to attain 5%–10% of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC), | |

| Based on (Natsume et al., 2015) | |||||

BFR and aerobic activities

The use of BFRT during walking has been shown to enhance physiological and functional benefits (Abe, Kearns, & Sato, 2006; Clarkson, Conway, & Warmington, 2017; Smith, Scott, Girard, & Peiffer, 2022) as well as been shown feasible for individuals with Knee osteoarthritis (OA) with significant improvements in physical performance, albeit not improving self-reported knee function (KOOS) (Petersson, Langgård Jørgensen, Kjeldsen, Mechlenburg, & Aagaard, 2022). Furthermore BFRT have shown to enhance endurance athlete’s maximal rate of oxygen consumption (V̇O2max), onset of blood lactate accumulation (OBLA), and economy of motion (Smith et al., 2022).

Also, in recreationally active individuals, 4 weeks of cycling (15 minutes, 40% V̇O2max) with continuous BFR resulted in a 7.7% increase in maximal knee-extensor force production (i.e., strength) that the authors attributed to a 5.1% increase in quadriceps cross-sectional area (Abe et al., 2010).

Recommendations for the use of BFR and aerobic activities after ACLR.

- Frequence: 2-4 times per week

- Load: 40-60-80% LOP

- Time: 10-20 minutes before or after the session

- Target: Patient that has not been given green light for running.

Example of walking

| Exercise | Set, reps, time | Load | Tempo | Comments |

| Walking | 15 minutes, 4x per week | 60% of LOP | 4-6km/h | If speed is limitation inclination can be added |

| Based on (Abe et al., 2006; Clarkson et al., 2017; Petersson et al., 2022) | ||||

| Rowing | 2×10 minutes, 3x times per week for 5 weeks | 40-80% of LOP | Low intensity training (below an individual heart rate, which corresponds to a blood lactate concentration of 2mmol/L) | |

| Based on (Held, Behringer, & Donath, 2020; Smith et al., 2022) | ||||

| Bike | 15 minutes or

5 min on/2 min off x 2 |

40% of LOP or Add/increase resistance if <6/10 fatigue | 40% of VO2max or starting RPM to be discussed | |

| Based on Aspetar ACL group | ||||

BFR for pain

When applying BFRT we should be aware of how training programs are perceived and psychologically tolerated. Subjective perceptions influence a patient’s attitude toward BFRT and can affect the motivation and adherence to follow a given protocol.

Previous research from Aspetar has shown an immediate decrease in anterior knee pain in three functional tests (shallow squat, deep squat, and 20cm step down) after a single BFR-exercise bout and the effect sustained for at least 45 minutes (Korakakis, 2018) when compared to low-load resistance training.

Recommendations for the use of BFR for pain after ACLR.

- Frequence: Before the session

- Load: 60% LOP

- Time: 30-15-15-15

- Target: Patient that has a flear up.

Example of BFRT for pain

| Week | Exercise | Set, reps, time | Session per week | Load | Tempo |

| 4-13 | Leg extension | 30/15/15/15 reps | With same session | 80% of LOP | 2 seconds concentric, 2 seconds eccentric paced by a metronome |

| Based on (Korakakis, Whiteley, & Epameinontidis, 2018) | |||||

BFR and preoperative rehabilitation

It is recommended that preoperative rehabilitation might improve quadriceps strength, knee range of motion and may decrease the time to return to sport in order to educate the patient regarding the postoperative rehabilitation course (Kotsifaki et al., 2023).

However, no studies have yet investigated the preoperative BFR rehabilitation effect for ACLR, however we would recommend using BFR in patients that cannot tolerate heavy loading or having pain issues as similar way as ACLR.

BFR and tendon

A few studies have looked at the effect of BFR on tendons. One study found increased patellar cross sectional area (CSA) after 14 weeks of BFR intervention similar to high loading (Centner C, Jerger S, Lauber B, et al. Low-Load Blood Flow Restriction and High-Load Resistance Training Induce Comparable Changes in Patellar Tendon Properties. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2022). Similar trend was found with a three week intervention with BFR for chronic patella tendinopathy. Here leg extension and leg press used 3x per week at 20-40% of 1RM (Skovlund, SV, Aagaard, P, Larsen, P, et al. The effect of low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction on chronic patellar tendinopathy — A case series. Transl Sports Med. 2020). Similar, one study found that tendon morphology and mechanical properties can be increased after 14 weeks BFR intervention Centner C, Lauber B, Seynnes OR, et al. Low-load blood flow restriction training induces similar morphological and mechanical Achilles tendon adaptations compared with high-load resistance training. J Appl Physiol (1985). The author also found similar achilles tendon hypertrophy with ll-bfr as heavy load (Centner C, Jerger S, Lauber B, et al. Similar patterns of tendon regional hypertrophy after low-load blood flow restriction and high-load resistance training. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2023).

| Week | Exercise | Set, reps, time | Session per week |

| 14 weeks intervention for achilles tendon hypertrophy and morphology and mechanical properties | Seated and standing calf raise | 30-15-15-15 reps, LL-BFR 20-35% of 1 RM. 20% for first 4 weeks, increase 5% every 4 weeks until final load of 35% of 1RM. LOP was 50% | 3x per week, for 14 weeks |

| Based on ( Centner, 2023, 2019) | |||

| Week | Exercise | Set, reps, time |

| 14 weeks intervention for patella tendon morphology and mechanical properties | Bilateral leg press, knee extension an seated and standing calf raise. 20% for first 4 weeks, increase 5% every 4 weeks until final load of 35% of 1RM. LOP was 50% | 3x per week, for 14 weeks |

| 3 weeks intervention for chronic | Bilateral leg press, knee extension 20-40% of 1RM. | |

| Based on ( Centner, 2022, Skovgaard, 2019) | ||

Aim

The aim of this occlusion protocol is to present best evidence and clinical practice. We have tried to come up with different scenarios for when BFR restriction can be used. We have provided guidelines for precautions and when to start and criteria for when to stop using it.

This protocol allows a high degree of freedom for exercise selection either by exercise or by post-surgical week. However, your clinical judgment should be aligned with surgical restriction or ACL rehabilitation protocol. For shorter intervention in later phases of the rehab a high frequency for three is recommended for then to be evaluated again. Here protocols for including BFRT together with aerobic activities such as walking, rowing or biking. BFRT can also be used within the session for pain management in the beginning of the session to allow pain-free exercises. Practical BFRT can also be used to target 1–2 muscle group at the end of a heavy-load training session, as a finisher, to preferentially stress muscle fibers that may not be sufficiently stressed with the goal to improve muscle strength and muscle mass.

References

-

Abe, T., Fujita, S., Nakajima, T., Sakamaki, M., Ozaki, H., Ogasawara, R., . . . Ishii, N. (2010). Effects of Low-Intensity Cycle Training with Restricted Leg Blood Flow on Thigh Muscle Volume and VO2MAX in Young Men. J Sports Sci Med, 9(3), 452-458.

-

Abe, T., Kearns, C. F., & Sato, Y. (2006). Muscle size and strength are increased following walk training with restricted venous blood flow from the leg muscle, Kaatsu-walk training. J Appl Physiol (1985), 100(5), 1460-1466. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01267.2005

-

Bjørnsen, T., Wernbom, M., Kirketeig, A., Paulsen, G., Samnøy, L., Bækken, L., . . . Raastad, T. (2019). Type 1 Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy after Blood Flow-restricted Training in Powerlifters. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 51(2), 288-298. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000001775

-

Bond, C. W., Hackney, K. J., Brown, S. L., & Noonan, B. C. (2019). Blood Flow Restriction Resistance Exercise as a Rehabilitation Modality Following Orthopaedic Surgery: A Review of Venous Thromboembolism Risk. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 49(1), 17-27. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8375

-

Centner, C., Jerger, S., Lauber, B., Seynnes, O., Friedrich, T., Lolli, D., . . . König, D. (2023). Similar patterns of tendon regional hypertrophy after low-load blood flow restriction and high-load resistance training. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 33(6), 848-856. doi:10.1111/sms.14321

-

Clarkson, M. J., Conway, L., & Warmington, S. A. (2017). Blood flow restriction walking and physical function in older adults: A randomized control trial. J Sci Med Sport, 20(12), 1041-1046. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2017.04.012

-

de Queiros, V. S., de França, I. M., Trybulski, R., Vieira, J. G., Dos Santos, I. K., Neto, G. R., . . . Dantas, P. M. S. (2021). Myoelectric Activity and Fatigue in Low-Load Resistance Exercise With Different Pressure of Blood Flow Restriction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol, 12, 786752. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.786752

-

de Queiros, V. S., Dos Santos Í, K., Almeida-Neto, P. F., Dantas, M., de França, I. M., Vieira, W. H. B., . . . Cabral, B. (2021). Effect of resistance training with blood flow restriction on muscle damage markers in adults: A systematic review. PLoS One, 16(6), e0253521. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0253521

-

de Queiros, V. S., Rolnick, N., de Alcântara Varela, P. W., Cabral, B., & Silva Dantas, P. M. (2022). Physiological adaptations and myocellular stress in short-term, high-frequency blood flow restriction training: A scoping review. PLoS One, 17(12), e0279811. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0279811

-

de Queiros, V. S., Rolnick, N., Dos Santos Í, K., de França, I. M., Lima, R. J., Vieira, J. G., . . . Silva Dantas, P. M. (2022). Acute Effect of Resistance Training With Blood Flow Restriction on Perceptual Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Health, 19417381221131533. doi:10.1177/19417381221131533

-

Farup, J., de Paoli, F., Bjerg, K., Riis, S., Ringgard, S., & Vissing, K. (2015). Blood flow restricted and traditional resistance training performed to fatigue produce equal muscle hypertrophy. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 25(6), 754-763. doi:10.1111/sms.12396

-

Held, S., Behringer, M., & Donath, L. (2020). Low intensity rowing with blood flow restriction over 5 weeks increases V̇O(2)max in elite rowers: A randomized controlled trial. J Sci Med Sport, 23(3), 304-308. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.002

-

Hughes, L., Paton, B., Rosenblatt, B., Gissane, C., & Patterson, S. D. (2017). Blood flow restriction training in clinical musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med, 51(13), 1003-1011. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097071

-

Hughes, L., Rosenblatt, B., Haddad, F., Gissane, C., McCarthy, D., Clarke, T., . . . Patterson, S. D. (2019). Comparing the Effectiveness of Blood Flow Restriction and Traditional Heavy Load Resistance Training in the Post-Surgery Rehabilitation of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Patients: A UK National Health Service Randomised Controlled Trial. Sports Med, 49(11), 1787-1805. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01137-2

-

Jack, R. A., 2nd, Lambert, B. S., Hedt, C. A., Delgado, D., Goble, H., & McCulloch, P. C. (2022). Blood Flow Restriction Therapy Preserves Lower Extremity Bone and Muscle Mass After ACL Reconstruction. Sports Health, 19417381221101006. doi:10.1177/19417381221101006

-

Jakobsen, T. L., Thorborg, K., Fisker, J., Kallemose, T., & Bandholm, T. (2022). Blood flow restriction added to usual care exercise in patients with early weight bearing restrictions after cartilage or meniscus repair in the knee joint: a feasibility study. J Exp Orthop, 9(1), 101. doi:10.1186/s40634-022-00533-4

-

Keller, M., Faude, O., Gollhofer, A., & Centner, C. (2023). Can We Make Blood Flow Restriction Training More Accessible? Validity of a Low-Cost Blood Flow Restriction Device to Estimate Arterial Occlusion Pressure. Journal of strength and conditioning research, Publish Ahead of Print. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004434

-

Korakakis, V., Whiteley, R., & Epameinontidis, K. (2018). Blood Flow Restriction induces hypoalgesia in recreationally active adult male anterior knee pain patients allowing therapeutic exercise loading. Phys Ther Sport, 32, 235-243. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2018.05.021

-

Kotsifaki, R., Korakakis, V., King, E., Barbosa, O., Maree, D., Pantouveris, M., . . . Whiteley, R. (2023). Aspetar clinical practice guideline on rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Br J Sports Med. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-106158

-

Kubota, A., Sakuraba, K., Sawaki, K., Sumide, T., & Tamura, Y. (2008). Prevention of disuse muscular weakness by restriction of blood flow. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 40(3), 529-534. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815ddac6

-

Lepley, L. K., Davi, S. M., Burland, J. P., & Lepley, A. S. (2020). Muscle Atrophy After ACL Injury: Implications for Clinical Practice. Sports Health, 12(6), 579-586. doi:10.1177/1941738120944256

-

Minniti, M. C., Statkevich, A. P., Kelly, R. L., Rigsby, V. P., Exline, M. M., Rhon, D. I., & Clewley, D. (2020). The Safety of Blood Flow Restriction Training as a Therapeutic Intervention for Patients With Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review. Am J Sports Med, 48(7), 1773-1785. doi:10.1177/0363546519882652

-

Nakajima, K. (2006). THE EFFECT OF KNOWLEDGE ACCESSIBILITY ON INTERNATIONAL INCOME INEQUALITY. Review of Urban & Regional Development Studies, 18(2), 102-117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-940X.2006.00114.x

-

Nascimento, D. D. C., Rolnick, N., Neto, I. V. S., Severin, R., & Beal, F. L. R. (2022). A Useful Blood Flow Restriction Training Risk Stratification for Exercise and Rehabilitation. Front Physiol, 13, 808622. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.808622

-

Natsume, T., Ozaki, H., Saito, A. I., Abe, T., & Naito, H. (2015). Effects of Electrostimulation with Blood Flow Restriction on Muscle Size and Strength. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 47(12), 2621-2627. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000000722

-

Ohta, H., Kurosawa, H., Ikeda, H., Iwase, Y., Satou, N., & Nakamura, S. (2003). Low-load resistance muscular training with moderate restriction of blood flow after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Acta Orthop Scand, 74(1), 62-68. doi:10.1080/00016470310013680

-

Patterson, S. D., Hughes, L., Warmington, S., Burr, J., Scott, B. R., Owens, J., . . . Loenneke, J. (2019). Blood Flow Restriction Exercise: Considerations of Methodology, Application, and Safety. Front Physiol, 10, 533. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00533

-

Petersson, N., Langgård Jørgensen, S., Kjeldsen, T., Mechlenburg, I., & Aagaard, P. (2022). Blood Flow Restricted Walking in Elderly Individuals with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Feasibility Study. J Rehabil Med, 54, jrm00282. doi:10.2340/jrm.v54.2163

-

Prue, J., Roman, D. P., Giampetruzzi, N. G., Fredericks, A., Lolic, A., Crepeau, A., . . . Weaver, A. P. (2022). Side Effects and Patient Tolerance with the Use of Blood Flow Restriction Training after ACL Reconstruction in Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 17(3), 347-354. doi:10.26603/001c.32479

-

Rolnick, N., Kimbrell, K., Cerqueira, M. S., Weatherford, B., & Brandner, C. (2021). Perceived Barriers to Blood Flow Restriction Training. Front Rehabil Sci, 2, 697082. doi:10.3389/fresc.2021.697082

-

Rolnick, N., Kimbrell, K., & Queiros, V. (2022). Beneath the Cuff: Often Overlooked and Under-Reported Blood Flow Restriction Device Characteristics and their Potential Impact on Practice.

-

Rolnick, N., & Schoenfeld, B. (2020). Blood Flow Restriction Training and the Physique Athlete: A Practical Research-Based Guide to Maximizing Muscle Size. Strength and Conditioning Journal, Publish Ahead of Print, 1. doi:10.1519/SSC.0000000000000553

-

Scott, B. R., Loenneke, J. P., Slattery, K. M., & Dascombe, B. J. (2016). Blood flow restricted exercise for athletes: A review of available evidence. J Sci Med Sport, 19(5), 360-367. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.04.014

-

Slysz, J. T., Boston, M., King, R., Pignanelli, C., Power, G. A., & Burr, J. F. (2021). Blood Flow Restriction Combined with Electrical Stimulation Attenuates Thigh Muscle Disuse Atrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 53(5), 1033-1040. doi:10.1249/mss.0000000000002544

-

Smith, N. D. W., Scott, B. R., Girard, O., & Peiffer, J. J. (2022). Aerobic Training With Blood Flow Restriction for Endurance Athletes: Potential Benefits and Considerations of Implementation. J Strength Cond Res, 36(12), 3541-3550. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000004079

-

Spada, J. M., Paul, R. W., & Tucker, B. S. (2022). Blood Flow Restriction Training preserves knee flexion and extension torque following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. J Orthop, 34, 233-239. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2022.08.031

-

Takarada, Y., Takazawa, H., & Ishii, N. (2000). Applications of vascular occlusion diminish disuse atrophy of knee extensor muscles. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 32(12), 2035-2039. doi:10.1097/00005768-200012000-00011

-

Vanwye, W. R., Weatherholt, A. M., & Mikesky, A. E. (2017). Blood Flow Restriction Training: Implementation into Clinical Practice. Int J Exerc Sci, 10(5), 649-654.

-

Wengle, L., Migliorini, F., Leroux, T., Chahal, J., Theodoropoulos, J., & Betsch, M. (2022). The Effects of Blood Flow Restriction in Patients Undergoing Knee Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med, 50(10), 2824-2833. doi:10.1177/03635465211027296

[…] Blood flow restriction (BFR) after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) […]