Return to Sport after syndesmosis injuries

Introduction:

“When will I be playing again?” This is often the first question that comes to an athlete’s mind after an injury. However, answering this question for syndesmosis injuries can be tricky, as these injuries often lead to unpredictable recoveries. In a survey of physicians and athletic trainers who care for professional sports teams, syndesmosis was ranked as the most difficult foot and ankle injury to treat in professional athletes. Fortunately, syndesmosis injuries are not common in sports, with an overall incidence rate of 0.5 per 1000 hours of exposure, equivalent to an injury burden of 1.8 days of absence per 1000 hours of exposure, observed over 15 consecutive seasons of European professional football between 2001 and 2016. However, an imaging study suggests that up to 20% of acute ankle sprains involve the syndesmosis, and the prevalence of syndesmotic injuries may be underestimated.

Syndesmosis injuries are consistently associated with higher levels of disability and pain and can potentially take between 2 to 30 times longer to heal compared to isolated ligament sprains. Over the past few decades, most injury rehabilitation protocols have shifted away from strict time-based protocols to more criteria-based guidelines with clear discharge criteria. Programs are often individualized to the person’s injury, training status/experience, and expectations for rehab. Progression from one phase to the next only occurs when the patient meets specific clinical milestones. Management and outcomes of syndesmosis injuries are determined by the fracture grade and associated injury around the ankle, described on a spectrum from conservative management with non-operative immobilization to open reduction and internal fixation with a screw or fixation with a tightrope. Using dynamic fixation has been shown to reduce the number of complications along with improved clinical outcomes compared with static screw fixation. Dynamic fixation also has the advantage of not requiring hardware removal, which often needs to be removed after 8 to 12 weeks, leaving the athlete with a slight setback in their rehabilitation. However, a recent survey among surgeons has shown a wide variety of indications, treatments, device choices, as well as variability in the expected return to play. The diversity in approaches and post-operative recommendations highlights the need for better evidence-based guidelines to guide the management of syndesmotic injuries.

Diagnosing:

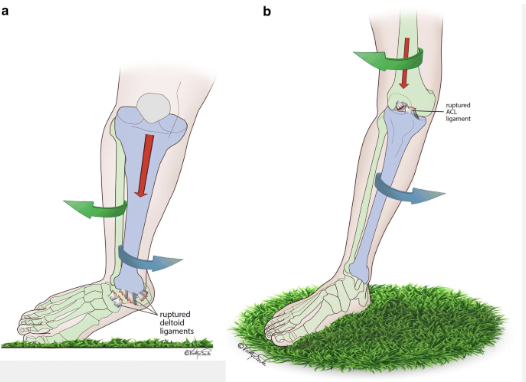

Although there is no clear classification system for the degree of ankle injuries to guide treatment or predict outcomes, a commonly used classification system is the West Point Ankle Grading System. The classification divides the injury into three grades:

- Grade I: Injuries with a sprain to the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL) without instability. This grade is managed non-surgically with a period of immobilization, reduced weight-bearing, and gradual rehabilitation.

- Grade II: Injuries where there is a severe ligamentous injury, including rupture of the AITFL and injury to the intraosseous ligament (IOL). Grade II injuries are particularly challenging when determining whether to pursue operative or non-operative treatment. A prospective study suggests that patients with a clinically stable syndesmosis (Grade IIa) were treated non-operatively, whereas unstable syndesmosis (Grade IIb) should be stabilized with surgical fixation.

- Grade III: Injuries with complete disruption of the syndesmosis, often associated with other injuries. These injuries typically require operative management using the mentioned methods.

A clinical diagnosis would include a Cotton test for laxity, pain provocation tests such as a positive squeeze test, external rotation test (both weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing), fibular translation test, as well as palpation for tenderness, also known as syndesmosis tenderness length.

Treatment

The goal of the rehabilitation process is to allow the athlete to safely return to sporting activity and function as quickly as possible while also minimizing the risk of re-injury to avoid future complications and chronic ankle instability (CAI).

There is little evidence for rehabilitation after syndesmosis injuries; however, the athlete often comes with restrictions set by the surgeon depending on the conservative approach or surgical procedure and the surgeon’s clinical experience. These restrictions are often based on the surgical procedure and post-surgical protocol implemented by the surgeons. Each surgery is slightly different and can influence the progression in the first phase of rehabilitation, so it is important to fully understand the surgical procedure.

The intent of early rehab is to stimulate the natural healing process of the ankle injury with a period of protected loading, which is recommended due to healing, pain, swelling, limited range of motion, and muscle control in order to limit muscle atrophy. Acute management should adhere to the general principles of POLICE (Protection, Optimal Loading, Ice, Compression, and Elevation) to ensure joint protection, pain and swelling reduction, and a gradual restoration of function. Training should focus on patient education, pain/swelling management, range of motion (ROM), motor control, and muscle strength to minimize the loss of muscle strength and volume around the ankle. It is important to keep the athlete active from a cardiovascular, physical, and mental standpoint. Cardiovascular activities increase cellular metabolic levels and enhance blood flow to the healing extremity. This can increase motivation and provide psychological benefits during recovery.

Typical rehabilitation is divided into three phases: early, mid, and late-stage rehabilitation. Each phase has specific goals, and advancement from one phase to the next depends on achieving these goals. However, a recent consensus statement recommended that return to sport should be aligned with the athlete’s sport and their level of participation. The consensus statement included three steps as part of the return to sport continuum: return to participation (modified training), return to sport (full training), and return to performance (competition level). Most regimens consist of a period of immobilization and restricted weight-bearing, progressing to the restoration of movement, strength, and proprioception, and finally sports-specific drills prior to returning to competition. Despite this standard approach, it has been observed that prolonged immobilization for ankle and syndesmosis injuries can result in sequelae, including muscle atrophy, arthrofibrosis, cartilaginous degeneration, bone atrophy, and ankle joint stiffness. In the following section, we will describe the different phases for conservative treatment and the surgical approach.

Phase 1

Early-stage rehabilitation focuses on soft tissue inflammation and edema. This phase emphasizes pain control, decreasing inflammation, and restoring normal joint ROM. Once these goals are accomplished, the patient is ready to progress to Phase II.

Immediately after the injury/surgery, the athlete will be given weight-bearing restrictions using a boot and crutches for protection and optimal loading. Dorsiflexion and eversion should be avoided to reduce the risk of applying unnecessary tension to the joint and the screw/tightrope. Ice, compression, and elevation will be recommended multiple times during the day. One case study described the use of a cooling and compression system in the acute phase before and after each session.

A prospective study on unstable syndesmosis (grade IIb) stabilized with a tightrope used a boot for 4 weeks, which included 1 week of non-weight-bearing, partial weight-bearing for 1 week, and full weight-bearing when pain-free. Ankle exercises to regain range of motion were encouraged from 10 days postoperatively; pool exercises and proprioceptive exercises were commenced from 3 weeks, and impact activities from 5 weeks postoperatively. Similarly, recommendations were used in a narrative review, including non-weight-bearing splinting for 10-14 days to allow wound healing and resolution of inflammation, with full weight-bearing commenced at 4 weeks as tolerated. A slightly different approach was used in a case series among professional rugby players, where the first 5 days postoperatively were spent in a plaster-of-paris (POP) boot, followed by 3 weeks in an Aircast boot, progressively increasing weight-bearing as pain and swelling allowed. The boot was removed for ankle sagittal plane range of motion exercises to avoid stressing the repair process until week 7, when subtalar joint mobilizations and range of motion exercises were performed in all directions. Furthermore, they performed isometric strengthening exercises in the plantar direction as well as foot intrinsic muscle exercises. Other exercises with the boot on and non-weight-bearing exercises were allowed to maintain the larger lower limb muscles (gluteal, quadriceps, and hamstrings). From week 3, static biking and ankle range of motion exercises in all directions were allowed (with caution not to force the movement). Other early exercises such as toe curls, straight leg raises, and knee bends to enhance blood circulation, and neuromuscular stimulation (NMES) were applied after 1 month to stimulate the vastus medialis oblique and gastrocnemius muscles without weight bearing.

To sum up the guidelines:

- Non-weight-bearing for 0-4 weeks

- General principles of POLICE (Protection, Optimal Loading, Ice, Compression, and Elevation)

- Pool exercises when the wound is healed

- Other exercises with the boot on and non-weight-bearing exercises were allowed to maintain the larger lower limb muscles (gluteals, quadriceps, and hamstrings) such as straight leg raises and knee bends

- NMES (neuromuscular stimulation) to stimulate muscles without weight-bearing

- Isometric strengthening exercises in the plantar direction

- Foot intrinsic muscle exercises

- Static biking from week 3 with caution not to force the movement

Phase 2

The focus of mid-stage rehabilitation is foot and ankle flexibility with functional strengthening. Cardiovascular conditioning, proprioceptive training, and light sport-specific functional training are initiated during this phase. Once these goals are completed, the athlete is ready for a gradual return to sporting activity.

The time frame for starting Phase II depends on the criteria above but is approximately 4-6 weeks after surgery. New exercises initiated during this phase include standing calf stretches, balance exercises, double-to-single leg calf raises, and stair climbing. Various discharge criteria in this phase have been used to progress to Phase III, such as the ability to perform single-leg balance for 60 seconds. In one case study, a 30-second single-leg balance was used as part of “The Comprehensive High-Level Activity Mobility Predictor (CHAMP-S),” which includes single-limb stance, Edgren side step test, T-test, and Illinois agility test criteria to enter return to sport. Besides this, other criteria have focused on restoring 80% of talocrural and subtalar ROM.

To sum up the guidelines:

- Foot and ankle flexibility with functional strengthening including standing calf stretches, double-to-single leg calf raises, and stair climbing

- Proprioceptive training with balance exercises

- Light sport-specific functional training initiated during this phase

- Cardiovascular conditioning

- Manual therapy in all directions with a goal of reaching 80% of talocrural and subtalar range of motion.

Phase 3

The final late-stage rehabilitation emphasizes a return to normal function and pre-injury sport-specific activity. Phase III is typically implemented two months after surgery with a focus on advanced strengthening of the entire lower extremity, flexibility, proprioception, and sport-specific agility drills. In a case study among professional rugby players, sports-specific running drills with functional and plyometric exercises started from week 7. The return-to-participation decisions were made by the physiotherapist, and the criteria were based on: ankle dorsiflexion back to pre-injury level (as per preseason testing or compared with the uninjured ankle) or 2 cm or less on the knee-to-wall test, symmetrical lower limb muscle strength, the ability to perform a symmetrical single-leg hop for height and length, and the ability to perform the star excursion balance test to pre-injury levels. Besides this, other criteria have been used, including normal gait, stability in single-leg balance, single-leg calf raises, deep catcher squats, two-legged and one-legged hops, jogging without limping in straight lines, curves, and sprinting distances, as well as carioca running, backward running, cutting, and position drills. In addition, to return to sport, one case report used baseline questionnaires from The Foot and Ankle Disability Index (FADI-ADL) and FADI Sport at 100%. These questionnaires have been found to be a good instrument to quantify functional disabilities in athletes with chronic ankle instability (CAI) throughout rehabilitation.

To sum up the guidelines:

- Symmetrical lower limb muscle strength

- Plyometric exercises with the goal of reaching symmetrical single-leg hop for height and length, jumping on two legs, and single-leg hop for 30 seconds or ten times

- Agility tests such as sprinting straight 40 yards (36m), running in figures of eight, carioca running for 40 yards, backward running, cutting, and position drills, or use of the CHAMP-S, which includes single-limb stance, Edgren side step test, T-test, and Illinois agility test

- The Foot and Ankle Disability Index (FADI-ADL) and FADI Sport questionnaire

- Functional training such as single-leg calf raises and deep catcher squats

- Cardiovascular conditioning

- Manual therapy in all directions with the goal of restoring ankle dorsiflexion to pre-injury level (as per preseason testing or compared with the uninjured ankle) or 2 cm or less on the knee-to-wall test

- Star excursion balance test to pre-injury levels

Conservative Management

The rehabilitation process for conservative, non-operative management generally follows a similar pattern for every injury, particularly in the acute management phase, using the POLICE principle as described earlier (17). However, there is limited literature available on clinical outcomes after conservative treatment of isolated syndesmotic injuries, indicating a lack of consensus. Despite this, most authors prefer a non-weight-bearing boot with a period of non-weight-bearing, as it has been reported to provide good long-term functional results (11).

In a prospective case series (1), treatment in the acute phase (72 hours) included immobilization, ice, compression, and electrotherapy, with weight-bearing as tolerated using walking boots and crutches. After the acute phase, the boot was removed, but weight-bearing was tolerated with crutches for 3-7 days. Similarly, a narrative review (9) recommended a short period of immobilization (1-4 days) in a boot and non-weight-bearing for 5-7 days to allow the acute inflammation and swelling to subside. Partial weight-bearing begins at 7-14 days post-injury as tolerated, while physiotherapy focuses on range of motion and light proprioceptive exercises. From 14 to 21 days, full weight-bearing is encouraged as tolerated, with strength training and proprioception exercises emphasized until pain-free single-leg support is achieved, usually around 6-8 weeks. Additionally, taping of the ankle was recommended for a minimum of 6 weeks during the rehabilitation phase after the boot was removed (9).

Another prospective study (13) recommends non-weight-bearing with an Aircast XP Walker boot for 10 days, after which athletes are allowed full weight-bearing as long as the ankle is pain-free. However, patients are instructed to wear the boot for a minimum of 3 weeks and then begin mobilizing the ankle without the boot, provided it remains pain-free. More conservative studies have recommended a longer period of immobilization, ranging from 2-6 weeks (11). A more controversial method to enhance outcomes in non-operative syndesmotic injury, according to one RCT study (21), evaluated the use of ultrasound-guided PRP injection in the AITFL. Athletes receiving PRP injections returned to play significantly sooner (19 days) with less pain. The return-to-sport criteria for both groups were based on functional goals such as complete static proprioception and balance tests, a single-leg jump of at least one meter, landing with a bent knee and deep ankle flexion, and completing a change-of-direction ability test. However, further study is warranted before PRP can be recommended as part of routine management options.

Guidelines Summary:

- Non-weight-bearing and boot for 0-7 days.

- Partial weight-bearing and boot for up to 2-6 weeks.

- General principles of POLICE (Protection, Optimal Loading, Ice, Compression, and Elevation).

- Include electrotherapy to stimulate healing.

- Functional exercises and light running at 6-8 weeks.

- Proprioceptive training with balance exercises to achieve 30 seconds of single-leg balance with closed eyes and single-leg jumps for 15 seconds.

- Complete a change-of-direction agility test before returning to play.

| Table 1 | Functional progression running | |||||||

| Day | ||||||||

| Week no. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Total minutes |

| 1 | 10 min | 0 | 10 min | 0 | 12 min | 0 | 14 min | 46 min |

| 2 | 0 | 16 min | 0 | 18 min | 0 | 20 min | 0 | 54 min |

| 3 | 25 min | 20 min | 0 | 25 min | 25 min | 0 | 30 min | 125 min |

| 4 | 30 min | 0 | 30 min | 35 min | 0 | 35 min | 40 min | 170 min |

| 5 | 0 | 40 min | 35 min | 0 | 45 min | 40 min | 45 min | 215 min |

Return to Sport

According to a systematic review (22), a 100% return to sport at the pre-injury level has been reported, although athletes who sustain a syndesmotic ankle sprain typically experience much longer recovery periods than those who sustain a lateral ankle sprain.

In a prospective 11-year follow-up study among professional football players in the Champions League (23), the report showed a mean lay-off of 15 ± 19 days for lateral ligamentous injury versus 43 ± 33 days for high ankle sprains (23). This was further supported by a recent epidemiological overview on isolated syndesmosis injuries in elite football, showing a mean absence of 39 days (SD 28 days) (2). Seven studies in the systematic review reported a mean return-to-sport time of 2 ± 15.8 days and 41.7 ± 9.8 days for operative and nonoperative management, respectively. In one prospective study (13) that included both grade IIa and IIb syndesmotic injuries, the mean return to sport was 45 days (23-63 days) in the nonoperative group and 65 days (range 27-104 days) in the operative group with tightrope repair. Similarly, a retrospective cohort study (3) on 110 football players comparing grade IIb with grade III injuries found that the time to begin sport-specific rehabilitation was 37 ± 12 days, the return to team training was 72 ± 28 days, and the first official match was played on average after 103 ± 28 days, with 95% of injured football players returning to match play within 6 months after surgery. Another case study on intercollegiate athletes treated operatively with 4.5-mm cortical screw fixation for grade III syndesmosis sprains (7) reported a return to play on average at 74 days (range 52-97 days). All patients had their screws removed once healing was complete. In a case report among elite rugby players with tightrope repair (5), the average return to sport was 64 days (SD 17.2, range 38–108), although one rugby player required an open reduction internal fixation and had a longer return to play (108 days RTP).

To our knowledge, there are no specific studies on the prevention of syndesmotic re-injury. However, general advice includes applying tape or a brace for prophylactic purposes during both practice and games in the first season of participation to help with proprioception and boost the athlete’s confidence (10,19).

Future Direction

Looking ahead to the future treatment of syndesmosis injuries, there may be a need to reevaluate our approach by not treating them as high ankle sprains, due to differing injury mechanisms and surgical treatments. As the above literature highlights, there is a gap in optimizing rehabilitation protocols, return-to-sport definitions, progression, and discharge criteria. To increase the chances of a successful and safe RTS, specific criteria should be developed to potentially reduce the time needed to return to play and minimize the risk of re-injury.

In addition to focusing on discharge criteria, other future directions in rehabilitation could include the use of blood flow restriction (BFR) and cross-education training, either separately or in combination. BFR has shown promising results as an adjunct in postoperative rehabilitation, demonstrating successful outcomes in various rehabilitation areas including knee arthroscopy (24), osteochondral fracture (25), early anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (26), and Achilles tendon rupture (27). Benefits include muscle hypertrophy, strength, power, functional outcomes, reduced pain, and improved mechanical and morphological properties of tendons (24,25,28–30). Furthermore, BFR has been shown to induce several synergistic physiological adaptations, including increased hormone production, enhanced cell signaling pathways related to muscle protein synthesis, and altered muscle fiber-type recruitment (27). Although these results are promising, it is crucial to assess each patient for signs and symptoms of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) early after syndesmosis surgery. Signs and symptoms may include unexplained swelling, pain, cramping or soreness, red or discolored skin, a feeling of warmth in the affected limb, shortness of breath, chest pain or discomfort, rapid heart rate, light-headedness or dizziness, or fainting, similar to other post-surgery conditions (27).

In addition to blood flow restriction, cross-education training for the non-fractured limb has been associated with improved strength and ROM after a distal radius fracture at 12 weeks post-fracture (31). Similar effects have been observed with heavy strength training of the non-injured leg after ACL reconstruction, demonstrating improvement in quadriceps muscle strength at 8 and 24 weeks in the injured leg if trained at least three times per week (32,33). These cross-education results may have important clinical implications for rehabilitation strategies after syndesmosis injuries, where early training is not possible.

Conclusion

Overall, syndesmotic injuries show a high rate of return to pre-injury levels in patients receiving both operative and nonoperative treatment. However, it is difficult to comment on whether there is a significant difference between management groups due to the lack of comparative studies and inconsistencies in outcome measures, rehabilitation protocols, and return-to-sport definitions. More research is needed to optimize rehabilitation, define return-to-sport criteria, and understand the prevention and long-term impact of syndesmosis injuries for both conservative and surgical approaches. Acknowledging the gaps in the literature provides many research opportunities for improving clinically meaningful outcomes and establishing discharge criteria that can allow athletes to return to sporting activity and function safely and quickly, while also minimizing the risk of re-injury and avoiding future complications such as chronic ankle instability (CAI).

Reference

- Miller BS, Downie BK, Johnson PD, Schmidt PW, Nordwall SJ, Kijek TG, m.fl. Time to return to play after high ankle sprains in collegiate football players: a prediction model. Sports Health. november 2012;4(6):504–9.

- Lubberts B, D’Hooghe P, Bengtsson H, DiGiovanni CW, Calder J, Ekstrand J. Epidemiology and return to play following isolated syndesmotic injuries of the ankle: a prospective cohort study of 3677 male professional footballers in the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Br J Sports Med. august 2019;53(15):959–64.

- D’Hooghe P, Grassi A, Alkhelaifi K, Calder J, Baltes TPA, Zaffagnini S, m.fl. Return to play after surgery for isolated unstable syndesmotic ankle injuries (West Point grade IIB and III) in 110 male professional football players: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 31 2019;

- Roemer FW, Jomaah N, Niu J, Almusa E, Roger B, D’Hooghe P, m.fl. Ligamentous Injuries and the Risk of Associated Tissue Damage in Acute Ankle Sprains in Athletes: A Cross-sectional MRI Study. Am J Sports Med. juli 2014;42(7):1549–57.

- Latham AJ, Goodwin PC, Stirling B, Budgen A. Ankle syndesmosis repair and rehabilitation in professional rugby league players: a case series report. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2017;3(1):e000175.

- Sman AD, Hiller CE, Rae K, Linklater J, Black DA, Refshauge KM. Prognosis of ankle syndesmosis injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. april 2014;46(4):671–7.

- Taylor DC, Tenuta JJ, Uhorchak JM, Arciero RA. Aggressive Surgical Treatment and Early Return to Sports in Athletes with Grade III Syndesmosis Sprains. Am J Sports Med [Internet]. 1. november 2007;35(11):1833–8. Tilgængelig hos: https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546507304666

- Grassi A, Samuelsson K, D’Hooghe P, Romagnoli M, Mosca M, Zaffagnini S, m.fl. Dynamic Stabilization of Syndesmosis Injuries Reduces Complications and Reoperations as Compared With Screw Fixation: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Sports Med. marts 2020;48(4):1000–13.

- McCollum GA, van den Bekerom MPJ, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Calder JDF, van Dijk CN. Syndesmosis and deltoid ligament injuries in the athlete. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc Off J ESSKA. juni 2013;21(6):1328–37.

- Jelinek JA, Porter DA. Management of unstable ankle fractures and syndesmosis injuries in athletes. Foot Ankle Clin. juni 2009;14(2):277–98.

- Schnetzke M, Vetter SY, Beisemann N, Swartman B, Grützner PA, Franke J. Management of syndesmotic injuries: What is the evidence? World J Orthop [Internet]. 18. november 2016;7(11):718–25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5112340/

- Hunt K, Challa S, D’Hooghe P, Kumparatana P, Phisitkul P, McCormick J, m.fl. The Evolving Approach to Treating Syndesmotic Injuries in the Elite Athlete: An International Perspective. Foot Ankle Orthop [Internet]. 1. oktober 2019;4(4):2473011419S00034. https://doi.org/10.1177/2473011419S00034

- Calder JD, Bamford R, Petrie A, McCollum GA. Stable Versus Unstable Grade II High Ankle Sprains: A Prospective Study Predicting the Need for Surgical Stabilization and Time to Return to Sports. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg Off Publ Arthrosc Assoc N Am Int Arthrosc Assoc. april 2016;32(4):634–42.

- van Dijk CN, Longo UG, Loppini M, Florio P, Maltese L, Ciuffreda M, m.fl. Classification and diagnosis of acute isolated syndesmotic injuries: ESSKA-AFAS consensus and guidelines. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc Off J ESSKA. april 2016;24(4):1200–16.

- D’Hooghe P, York PJ, Kaux JF, Hunt KJ. Fixation Techniques in Lower Extremity Syndesmotic Injuries. Foot Ankle Int. november 2017;38(11):1278–88.

- Tampere T, D’Hooghe P. The ankle syndesmosis pivot shift “Are we reviving the ACL story?” Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc Off J ESSKA. 25. april 2020;

- Bleakley CM, Glasgow P, MacAuley DC. PRICE needs updating, should we call the POLICE? Br J Sports Med. marts 2012;46(4):220–1.

- Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders A, Witvrouw E, Clarsen B, Cools A, m.fl. 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med. juli 2016;50(14):853–64.

- Ricci RD, Cerullo J, Blanc RO, McMahon PJ, Buoncritiani AM, Stone DA, m.fl. Talocrural Dislocation With Associated Weber Type C Fibular Fracture in a Collegiate Football Player: A Case Report. J Athl Train [Internet]. 2008;43(3):319–25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2386426/

- Feigenbaum LA, Kaplan LD, Musto T, Gaunaurd IA, Gailey RS, Kelley WP, m.fl. A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO THE REHABILITATION OF A COLLEGIATE FOOTBALL PLAYER FOLLOWING ANKLE FRACTURE: A CASE REPORT. Int J Sports Phys Ther. juni 2016;11(3):436–49.

- Laver L, Carmont MR, McConkey MO, Palmanovich E, Yaacobi E, Mann G, m.fl. Plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) as a treatment for high ankle sprain in elite athletes: a randomized control trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc Off J ESSKA. november 2015;23(11):3383–92.

- Vancolen SY, Nadeem I, Horner NS, Johal H, Alolabi B, Khan M. Return to Sport After Ankle Syndesmotic Injury: A Systematic Review. Sports Health. april 2019;11(2):116–22.

- Waldén M, Hägglund M, Ekstrand J. Time-trends and circumstances surrounding ankle injuries in men’s professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med. august 2013;47(12):748–53.

- Tennent DJ, Hylden CM, Johnson AE, Burns TC, Wilken JM, Owens JG. Blood Flow Restriction Training After Knee Arthroscopy: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Clin J Sport Med Off J Can Acad Sport Med. maj 2017;27(3):245–52.

- Loenneke JP, Young KC, Wilson JM, Andersen JC. Rehabilitation of an osteochondral fracture using blood flow restricted exercise: a case review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. januar 2013;17(1):42–5.

- Hughes L, Rosenblatt B, Haddad F, Gissane C, McCarthy D, Clarke T, m.fl. Comparing the Effectiveness of Blood Flow Restriction and Traditional Heavy Load Resistance Training in the Post-Surgery Rehabilitation of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Patients: A UK National Health Service Randomised Controlled Trial. Sports Med Auckl NZ. november 2019;49(11):1787–805.

- Bond CW, Hackney KJ, Brown SL, Noonan BC. Blood Flow Restriction Resistance Exercise as a Rehabilitation Modality Following Orthopaedic Surgery: A Review of Venous Thromboembolism Risk. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. januar 2019;49(1):17–27.

- Korakakis V, Whiteley R, Giakas G. Low load resistance training with blood flow restriction decreases anterior knee pain more than resistance training alone. A pilot randomised controlled trial. Phys Ther Sport Off J Assoc Chart Physiother Sports Med. november 2018;34:121–8.

- Yow BG, Tennent DJ, Dowd TC, Loenneke JP, Owens JG. Blood Flow Restriction Training After Achilles Tendon Rupture. J Foot Ankle Surg Off Publ Am Coll Foot Ankle Surg. juni 2018;57(3):635–8.

- Centner C, Lauber B, Seynnes OR, Jerger S, Sohnius T, Gollhofer A, m.fl. Low-load blood flow restriction training induces similar morphological and mechanical Achilles tendon adaptations compared with high-load resistance training. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md 1985. 1. december 2019;127(6):1660–7.

- Magnus CRA, Arnold CM, Johnston G, Dal-Bello Haas V, Basran J, Krentz JR, m.fl. Cross-education for improving strength and mobility after distal radius fractures: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. juli 2013;94(7):1247–55.

- Papandreou M, Billis E, Papathanasiou G, Spyropoulos P, Papaioannou N. Cross-exercise on quadriceps deficit after ACL reconstruction. J Knee Surg. februar 2013;26(1):51–8.

- Harput G, Ulusoy B, Yildiz TI, Demirci S, Eraslan L, Turhan E, m.fl. Cross-education improves quadriceps strength recovery after ACL reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc Off J ESSKA. januar 2019;27(1):68–75.